Reader’s log, March 2025

Orlando Reade’s “What in Me Is Dark: The Revolutionary Afterlife of Paradise Lost” makes the (to me) startling argument that Milton’s 17th Century epic poem has had and still has a reverberating political impact not merely in England but around the world.

If I thought about “Paradise Lost” at all before reading Reade’s book, I would have said that the only impact “Paradise Lost” has had in my lifetime was on college freshmen thrashing through it in English Lit 101 — a dwindling population.

Certainly my own experience of reading “Paradise Lost” was far from impactful: Basically it was a speed bump on my way through the reading required of an English major. It was better than “The Faerie Queene,” worse than “Beowulf,” quickly set aside and forgotten. I walked away from it with the enduring memory of one line only: “Better to reign in hell, than to serve in heaven.” (Of course.)

(Charmingly, Reade admits that his own undergraduate experience of reading “Paradise Lost” was much the same as mine.)

But Reade, now in possession of a PhD and, more interestingly, having several years of experience teaching in prisons, explains the ways that Milton’s work has influenced figures as diverse as Thomas Jefferson, Malcolm X, Hannah Arendt, and even Canadian academic and bro-verse shit-stirrer Jordan Peterson.

I will say that Reade’s subtitle somewhat oversells the concept. Revolutionary as “Paradise Lost” may have been, Milton himself was even more so, arguing for wider personal liberties (in particular, the right to divorce), and for freedom of thought, expression, and religion. Most dangerously for himself, he sided against King Charles in the English Civil War, which could have resulted in his death. In the end it was Charles who lost his head, not Milton. And although England’s monarchy was restored roughly a decade later, the seeds of modern democracy and civil rights had taken root.

Based on my reading of Reade’s book, my take is that Milton’s revolutionary activity and treatises, not his poetry per se, influenced Jefferson and many other figures.

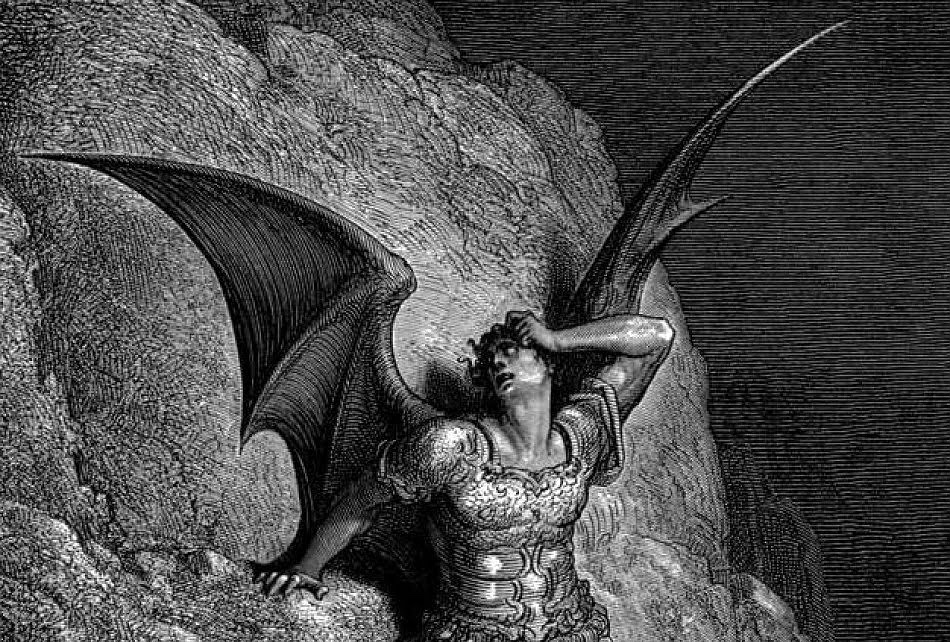

But as a literary and quasi-religious text, Milton’s composition has had a gigantic impact on the way we think about God and the Devil, and even about good and evil.

“Paradise Lost” is now a kind of adjunct to the Bible, basically providing a backstory to the book of Genesis, mapping Heaven and Earth and Hell, and even more importantly creating the character of Satan, who barely is mentioned in the Bible — or, in fact, is not really mentioned at all, because the word is actually a term for an adversary, not really a specific personage or angel. With “Paradise Lost,” Milton provides a structure for imagining a cavalcade of devils, a topography of hell, and a sense of the earth between heaven and hell.

There were many imagined devils before Milton, and many imagined hells, (Dante Alighieri composed “The Divine Comedy” hundreds of years before Milton was born) but Milton’s vision is the one that has most stuck with us, at least in the English-speaking word.

If you asked the average Joe, I would bet that he would say much of what is described in “Paradise Lost” is found in the Bible, which is not the case.

Of course I did not merely read “What in Me Is Dark,” I also got a copy of “Paradise Lost” itself — a nice Penguin Classics hardcover with an eerie cover design featuring hands reaching downward — and read it ever so slowly, not because I was savoring the text but because I found it awfully slow and wordy, and because I tend read in bed at night, I kept falling asleep.

I slept pretty well in March. Sorry, Mr. Milton!

I’m sure it doesn’t reflect well on me that I found “Paradise Lost” so tiresome. Surely (I would think) the writing is so sublime that the pages would swim by! It’s so quotable! The figure of Satan is so appealing!

It is certainly true that the writing is sublime, and sublimely quotable. Reading from a list of quotations from the text on the goodreads site is uplifting and amazing:

What hath night to do with sleep?

***

Long is the way and hard, that out of Hell leads up to light.

***

Which way I fly is hell; myself am hell;

And in the lowest deep a lower deep,

Still threat’ning to devour me, opens wide,

To which the hell I suffer seems a heaven.

I read these and other quotes and feel a surge of energy—this is that rare kind of writing that makes me want to write.

And yet that was not my reaction while reading the text itself.

Why? I’m not really sure. But a big problem for a modern reader is the indirect path of the story (it’s far from linear), and Milton’s sheer ambition, which seemed to drive him to include in the poem practically every bit of human knowledge he possessed.

“Paradise Lost” is constantly digressive and almost absurdly allusive. No action is described without comparing it to some other mythical or mythohistorical parallel. The phrase “as when” occurs again and again in the text, each time calling up a complicated metaphor:

As when the Tartar from his Russian foe,

By Astracan, over the snowy plains,

Retires; or Bactrin Sophi, from the horns

Of Turkish crescent, leaves all waste beyond

The realm of Aladule, in his retreat

To Tauris or Casbeen: So these, the late

Heaven-banished host, left desert utmost Hell

Many a dark league, reduced in careful watch

Round their metropolis

Oof. Note that in this sentence, the comparison to the Tartar and the Bactrin Sophi (the who?) does nothing to help the reader see or comprehend the actions of the fallen angels — it’s really just a flung-away allusion, a geohistorical name check.

He may have felt the need for so many extra doses of reference because “Paradise Lost,” unlike the earlier epics, is long on background explication but short on actual event. The plot is thin. It would make up barely a book or two of “The Odyssey” or “The Aeneid.”

And then there is the characterization. Everyone knows that Satan is the most interesting character in the poem. That’s a given. What isn’t said is that all the other characters are eye-wateringly dull. Adam is a simp. Eve is a dope. Michael the Angel is a bore. “The Son” is self-satisfied. God himself is essentially a set of stage directions.

I wonder if my response to the poem would have been more positive had I been in a class taught by Orlando Reade. He is passionate about his subject and he seems to have inspired his imprisoned, modern-day American students to think deeply about the text of what must be said to be a thorny and very long poem. Impressive! For me, I was more interested in the reverberations of “Paradise Lost” than I was in the text itself.

In the end, I suppose my failure to appreciate Milton is my fault, not his.

But I can’t help but assign him a little of the blame, too.

Leave a comment