The final novel of Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet, “Summer,” appeared late in 2020 and was notable, among other reasons, for having been written and published swiftly enough to incorporate the global pandemic into the plot.

“Autumn” was the first of the quartet to be published, and it too had a notably rapid turnaround, with references to the Brexit argument. The book was published around the time of the vote.

The apparent rush to publication is odd, given the quiet, thoughtful nature of the book, the slowness of the pacing, and most of all the lack of timeliness otherwise. The story, to the extent that there is one, could take place really at any point in the last 50 plus years.

So I would say It was a bit of a publisher’s parlor trick to get it out so fast. The writing of it, not so much. For a writer like Smith, whose output is building up to a Joyce Carol Oates-ian mass, it would be no great trick to snap off a novel in the space of five or six months, or, who knows, maybe less.

That’s not to say that “Autumn” reads in any way as rushed or sloppy. It’s quiet and contemplative. The sentences are trim and direct. It’s short on plot and even event, and there’s nothing wrong with that, especially for a novel that is meant to investigate the idea of time, but for me it falls short as a work of art because even though it presents as an experiment of form, the novel really hangs on the triangular relationship of a very old man, a young girl who is his neighbor, and the girl’s mother. And those relationships, especially the old man and the young girl, read as patently false. The man is prone to elfin wordplay, the girl solemnly adores their time together for no apparent reason, although I suppose the reasoning is that the mother is negligent, ergo of course the little girl will enjoy the company of her cloying, self-delighted neighbor. Ugh.

I stand for nothing if not truth in characterization, and by extension truth in relationships. The relationships in this book ring false. The characters are meant to define ideas, rather than themselves, and their relationships are used as a way of shining light on those ideas, rather than presented as extensions of the characters themselves. So again I say ugh.

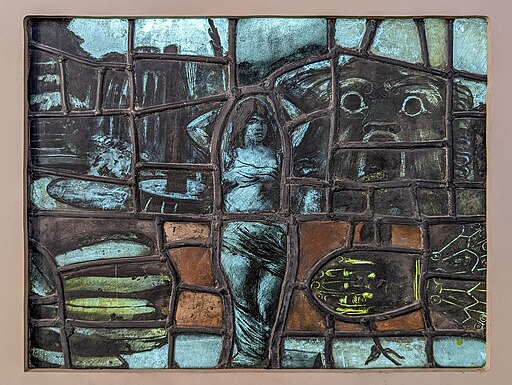

There is one shiveringly beautiful section during which the old man describes a painting. It’s really a beautiful moment, a page or two that draws you in. In that moment I too was enchanted by the old man, imagining (what I assumed to be) an imagined painting, created for the girl to consider in her mind. Very nice!

As it happens, that crystalline moment of the book is a sort of storytelling hinge. The painting is in fact a real-world painting by a real-life painter named Pauline Boty, a pop artist apparently overlooked by critics of the time and thereafter as a result of systemic sexism, about whom the girl grows up to write for her advanced degree. I was intrigued by Boty–I hadn’t heard of her and I imagine yes, she was overlooked for reasons of sex–but the details of her story just seemed whirled into the book for no particular reason.

Autumn is a smart book, sentence-by-sentence beautiful, but false in its heart. I will certainly read more Ali Smith, though, for she is clearly brilliant. But if she is going to write about people she needs to get it down a little better.

Photo credit: “Siren,” stained glass by Pauline Boty, c. 1958-62, via Wikimedia Commons

Leave a comment